|

Away From Japan, Tsunami's Effect Is Diffuse

Saturday, March 12, 2011

credit: By HENRY FOUNTAIN, The New York Times

The powerful earthquake that struck off the coast of Japan on Friday set off tsunami warnings around the Pacific Rim, including in Hawaii and California, but the vast majority of destructive flooding occurred in Japan itself, in the area nearest the quake's epicenter.

Tsunami experts said the pattern was not unusual. With earthquakes like the one in Japan, essentially two tsunamis are generated -- one that hits the nearest coastline, often within minutes, and another that can travel for thousands of miles in the opposite direction.

The wave that hits the nearby coastline first is usually the most destructive, said Eric Geist, a scientist with the United States Geological Survey. But with the tsunamis that head out to sea, some of the energy dissipates as the wave spreads outward across open ocean, like a ripple from a rock thrown into a pond. Coastal features can then either reduce or amplify some of the energy as the wave reaches land.

"Once the first wave hits the coastline, it gets very complicated," Dr. Geist said.

Reports from Sendai, the city in Japan closest to the quake, suggested that wave heights reached more than 12 feet above normal as the first tsunami wave struck.

Waves in parts of Hawaii reached seven feet above normal, damaging piers and marinas and causing some flooding. But by midmorning, sunbathers had returned to Waikiki Beach, though in smaller numbers than usual. Here and there, children ventured into the water, despite official warnings to stay out.

In North America, the Coast Guard said that one person was swept to sea near McKinleyville, Calif., while trying to take pictures of the approaching waves. A search had begun.

Four people were also swept to sea in Curry County, Ore., overtaken as they, too, were watching the waves. Two managed to get back to shore, officials said, while the others -- one of whom almost drowned -- were rescued.

In California, powerful waves sank several boats in Santa Cruz Harbor, about 60 miles southeast of San Francisco on Monterey Bay, ripping up docks and sending debris speeding toward shore. Sailboats broke free of their moorings and slammed against docks, bridges and other boats.

Laura K. Furgione, deputy assistant administrator of the National Weather Service, said that waves greater than eight feet above normal were reported in Crescent City, Calif. But about 90 miles south, at Humboldt Bay, the West Coast and Alaska Tsunami Warning Center reported waves only about three feet above normal.

Because of the complicated interactions with the coast as wave after wave strikes after traveling great distances, experts said, the impact of a tsunami can be highly variable. "Every place is unique," said Vasily Titov, director of the Center for Tsunami Research, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Given those variations, tsunami experts warned that predicting wave heights was difficult. "Tsunamis are rare events," said Paul Huang, a seismologist with the tsunami warning center. "And calibrating the big events is hard. You have no data."

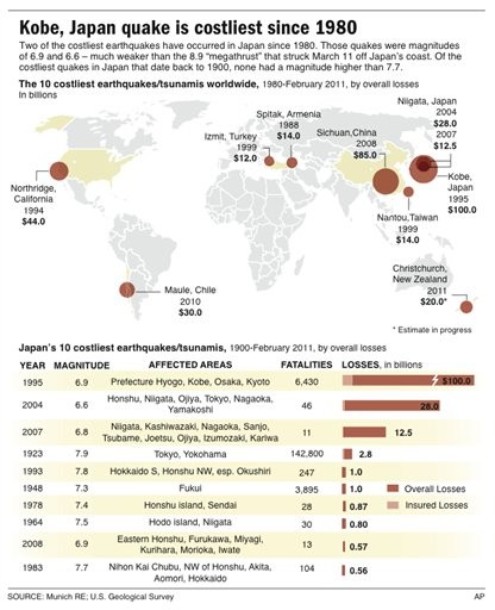

The magnitude 8.9 earthquake on Friday, the largest ever recorded in Japan, occurred in a subduction zone, where one of the earth's tectonic plates is sliding beneath another. In this case, the Pacific plate is sliding beneath an extension of the North American plate, which the Japanese island of Honshu sits on, at a rate of slightly more than 3 inches per year.

Between the two plates, stresses build up that are held in check by friction. At some point, said Ross S. Stein, a geophysicist with the geological survey, "the stress overwhelms that friction," and a rupture occurs.

In a subduction earthquake, parts of the fault zone are uplifted, while others dip down. "It's almost like you took a rug and kind of popped it and watched a ripple roll through it," Dr. Stein said.

If the quake occurs underwater, as the one in Japan did, the up-and-down movement displaces an enormous amount of water, setting off the tsunami.

David Applegate, senior science adviser for earthquakes at the geological survey, said during a conference call with reporters that the rupture occurred along a section of the fault zone about 180 miles long and 50 miles wide, "a very significant patch of the earth's crust." He said the rupture represented a "lurching" across the fault surface of about 50 feet.

The magnitude 8.9 earthquake was preceded by what seismologists call foreshocks, including a magnitude 7.2 quake that occurred Wednesday about 25 miles south of the epicenter on Friday. Technically, Dr. Applegate said, the magnitude 8.9 quake was an aftershock. It is rare, though not unheard of, to have an earthquake followed by a larger aftershock.

Dr. Applegate said the magnitude 8.9 earthquake released about 30 times as much energy as the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. He described the Japanese quake as a "low probability, high consequence" event.

"They only happen every few hundred years, perhaps," Dr. Applegate said, "but when they do happen, the results are catastrophic."

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

| จากคุณ |

:

july 19

|

| เขียนเมื่อ |

:

12 มี.ค. 54 13:25:22

|

|

|

|

|