|

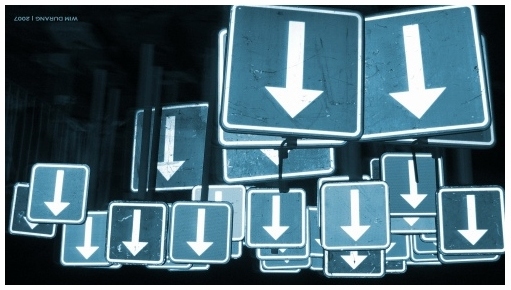

Greece: This cannot end well

By Ben Rooney @CNNMoney September 30, 2011: 1:50 PM ET

NEW YORK (CNNMoney) -- The debt crisis in Greece cannot end well.

That seems to be the general consensus among investors, economists and academics.

Even though global financial markets showed some resilience this week, the tone remains cautious as the underlying problems haven't changed.

"There is no way to avoid pain for Greece," said Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg Bank. "The austerity is painful. Further painful structural reforms are on their way."

There are essentially two options: Greece can continue to cut spending and raise taxes in a painful attempt to convince creditors that it can change its ways. Or, the country can admit defeat, default on its debts, and hope for the best.

Euro area leaders have said repeatedly that a default is off the table, arguing that such an outcome would have severe and unknowable consequences for the euro currency and the global financial system.

Euro crisis: 5 things you need to know

But there is also a growing recognition that the status quo is not working.

Over the past 15 months, the Greek government has cut wages for civil servants, raised taxes, reduced pension payments and furloughed thousands of workers.

In exchange, Greece has received billions of euros in emergency funding from the International Monetary Fund and other countries in the euro currency zone.

While the bailout money has kept a default at bay, many economists say the requisite austerity has pushed the Greek economy deeper into recession.

That's a problem because Greece will not be able to pay off its debts organically until its economy starts to grow again, something economists don't expect to happen for some time.

In many cases, Greece has delayed carrying the most painful reforms and critics say the government remains bloated and inefficient.

Yet the recent belt tightening has led to renewed strikes and protests in Athens, raising concerns that more austerity may be politically untenable for Greece.

At the same time, there is growing opposition in northern Europe to providing open-ended support for Greece. The worry among taxpayers in Germany, Finland and Austria is that the bailouts will never end.

All of this has culminated in a tense showdown between Greece and its benefactors at the IMF, European Commission and European Central Bank, known as the troika.

Euro stability fund is a mirage

Greece needs its latest installment of bailout money soon or it will run out of money by the middle of October. But the troika is not expected to make a decision until Oct. 13, according to German finance minister Wolfgang Schauble.

Hans-Joachim Voth, a professor of economic history at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, described the negotiations as a game of chicken, in which both sides are seeking to save face and buy time.

"Greece will probably get the next 8 billion tranche, but I think that will be the last one," he said.

Voth, like many economists, expects Greece to eventually default on its debts.

In theory, an organized default would allow Greece to get out of debt and take steps to boost its economic competitiveness.

Yes, a default would wipe out Greek banks and violate some European Union treaties. But it's better to "pull the plug" and move on than continue to delay the inevitable, they say.

"Restructuring is always a painful process and, even in the most positive scenario, it will be painful for Greece and cost other eurozone countries money," said Natascha Gewaltig, director of European economics for Action Economics in London. "But there is no alternative."

Gewaltig said there is a 50% chance that euro area authorities will manage a default in an organized way.

Then again, others warn a default could shock the global financial system at a time when economic activity around the world is slowing down.

Euro supporters say even a structured default by Greece could hit banks across Europe and drive up borrowing costs for other debt-stricken nations. The so-called contagion would be difficult to contain and could lead to a break up of the euro currency union.

"The best possible outcome for Greece is to stay the course, stay in the eurozone and return to growth when the structural reforms start to work and the austerity eases," said Schmieding.

Europe's debt crisis: Complete coverage

"Whether or not that includes an orderly restructuring of Greek debt makes only a very modest difference for Greece," he added. "One way or another, Greece will depend on foreign help -- and thus will have to meet conditions to qualify for such help."

In any event, the crisis has revealed fundamental flaws in the way the euro area operates.

Critics say having a shared currency without a coordinated approach to managing government debt was a bad idea to begin with. Others say allowing Greece, Portugal and other southern European nations into the club was a mistake.

The larger question, many analysts say, is will the 12 year old currency union be able to survive the crisis in its current form?

If Greece defaults, will it be forced out of the union? Will that drag down Italy and Spain? Could Germany abandon the euro out of frustration?

The answers to these questions may come in the next few months. For now, most experts agree that it's difficult to see a happy ending for Greece

| จากคุณ |

:

OASIS (Rain In The Sky)

|

| เขียนเมื่อ |

:

1 ต.ค. 54 15:21:34

|

|

|

|

|